In Deborah Poe’s new book, the author of Elements shifts her poetic researches from the building blocks of matter to the building blocks of memory. Her title, Keep, is both an archaic noun, the keep of a castle, and one of the commonest verbs. Keep is a command. It reminds us that remembering is not a choice. Each person’s memory is a vast, mostly unconscious construction, always already there, always changing, that can provide the materials for conscious constructions. Keep follows this trajectory—from neurobiology to inescapable memories to what we can make out of those memories—“every page more like a drawer, a compartment, or a box,” the verbal equivalent of El Lissitzky’s prouns, a high point in constructivist art.

In Deborah Poe’s new book, the author of Elements shifts her poetic researches from the building blocks of matter to the building blocks of memory. Her title, Keep, is both an archaic noun, the keep of a castle, and one of the commonest verbs. Keep is a command. It reminds us that remembering is not a choice. Each person’s memory is a vast, mostly unconscious construction, always already there, always changing, that can provide the materials for conscious constructions. Keep follows this trajectory—from neurobiology to inescapable memories to what we can make out of those memories—“every page more like a drawer, a compartment, or a box,” the verbal equivalent of El Lissitzky’s prouns, a high point in constructivist art.

Michael Ruby

Where poetry meets Zen meets neuroscience, keep maps the magical space of the Middle Way, in which phenomena arise and disappear continuously. Arranged in four interrelated sections, “cartography,” “coordinates,” “signs,” and “prouns,” Poe’s cosmopolitan charms loop back and echo as dream-like traces of memory, of being alive. Mapping a “sensual infrastructure” beyond our naming, “the way memories reside between now and letter after,” Poe’s is the music we need now, the “song on the stairs in the middle of the night.”

Ethel Rackin

“Keep” (the word implies duration, continuity, safety) does what poetry is supposed to do: take you further and deeper than mind, senses, and language ordinarily will. Memory, space, place, perception, personhood, fold and unfold in these careful poems, honed by fearless exploratory intelligence. “You don’t have to understand. What is lost when you ask why.”

Norman Fischer

How the body holds and releases experience, how sensory becomes sensuous, how perception informs memory with meaning—all of this is disclosed from the interiority Deborah Poe explores in keep. These intense and pensive poems model how perception directs us to what matters in this, the ephemeral moment of our perceiving (“Presence flutters why in the meaning(less).” Poe writes that body “and future exacerbate each other,” and the reader feels the ache—part elegiac and part erotic. In that tension these poems find an interplace in which “over and over windows burst wide open.”

Elizabeth Robinson

Deborah Poe’s the last will be stone, too is wildly ambitious and gorgeously successful–a series of poems based on artwork engaging somehow with death, from artists as diverse as Andres Serrano and the fashioners of Tutankhamen’s funeral collar. The poems enact for us a vision of human consciousness contemplating its own end. It’s a vision always aware of both our ability to evade the knowledge of mortality and the strength of our spirits in the face of its persistence. In this tension we locate our humanness; as Poe writes, “I pulled at the center of you,/and life came spilling out” (“Les Feuilles Mortes”). Using all the tools of the page’s architecture, the occasional borrowed text, and her considerable lyric gifts and intellect, Poe makes of her bardo journey a metaphysical tightrope walk without a net, one I look forward to making with her again and again. I know of few poets who would dare to tackle such subjects tackle head-on; I know none who would emerge from the struggle so triumphant as Poe.

Suzanne Paola

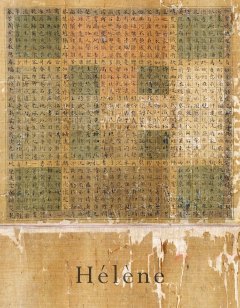

Deborah Poe’s 19th century heroine Hélène finds herself in the elaborate trap of a ‘factory-convent,’ manufacturing silk in western France—and her only release is the fantasy of producing it, instead, in China. Poe handles the implications and associations of these very different worlds with wrenching clarity. But finally, it is language—’We all our song within which voice finds its own escape’—that offers the window through which Hélène, and we, effect that escape. Poe’s handling of language throughout the book is nothing less than liberating, and yet it’s also arresting—it’s often, in short, simply breathtaking, while her acrobatically precise and dynamic balance between research and attention allows the reader to be simultaneously transported beyond and riveted to the present. A major accomplishment, and a haunting one.

Cole Swensen

Deborah Poe’s brilliant poems, grounded in 39 of our elements, catch us off balance in ways that create new balance. Her voices are humorous, prophetic, weird, and familiar: “4 empty green chairs by the ungoing hair fire heave, / wear her fire fire burning bright the half poison night.” Elements is a huge, strange, necessary book that takes us sometimes where we would not go. I think she’s a terrific poet.

Jean Valentine

“But that’s what it wasn’t like/sometimes”: in Poe’s marvelous poems the lit and the oblique delineate the textures of the never-knowable and the known. A restless and irresistible intelligence meets an exquisitely nuanced sense of the senses. The sensual and the metaphysical, Feeling and Thinking, what she names “the sensual infrastructure” and a “parenthetical ontology,” everywhere intersect. A poetic version of what wine connoisseurs call mouthfeel—the sensation on the tongue—is in every line of this book, “dada and blahblah,” the tongue’s rejoicing in consonant and vowel. Pound’s names for the powers of poetry—melopoeia, logopoeia, phanopoeia: the music, the linguistic play, the sensory image—all smolder at a white heat throughout Poe’s stunning debut.

Bruce Beasley

A mouthful, an electric stumble, a well-spaced lunge, Poe’s formal inquiry into the laws of settlement is a study in line breaks and trust. She is looking for a ‘between’ between sense organs and the dispossessed. She finds it. You witness her do so poem after poem. Her mindful tongue gathers the sensual (blossoms, mirrors, lakelight) refusing to hide the limits of the body within ideology. Neither Mother nor Mondrian could have structured such exquisite brushes with breath. These poems tremble like woodwinds, but Poe’s hands are on a grand piano pushing what is said against what is not. If you like to read text as musical score, you’ll love how Poe lotions language, positions it as a grin, as clench—part thigh, part tassel, part treatise.

Lori Anderson Moseman

You must be logged in to post a comment.